Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes | Church of St. Anthony of the Germans – Interior, Madrid

This is one case in Madrid where you can’t have too much of a good thing. The 17th century Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes is completely covered in frescoes, from top to toe. The fresco on the ceiling dome is by Francisco Rizi. It depicts the Glory of

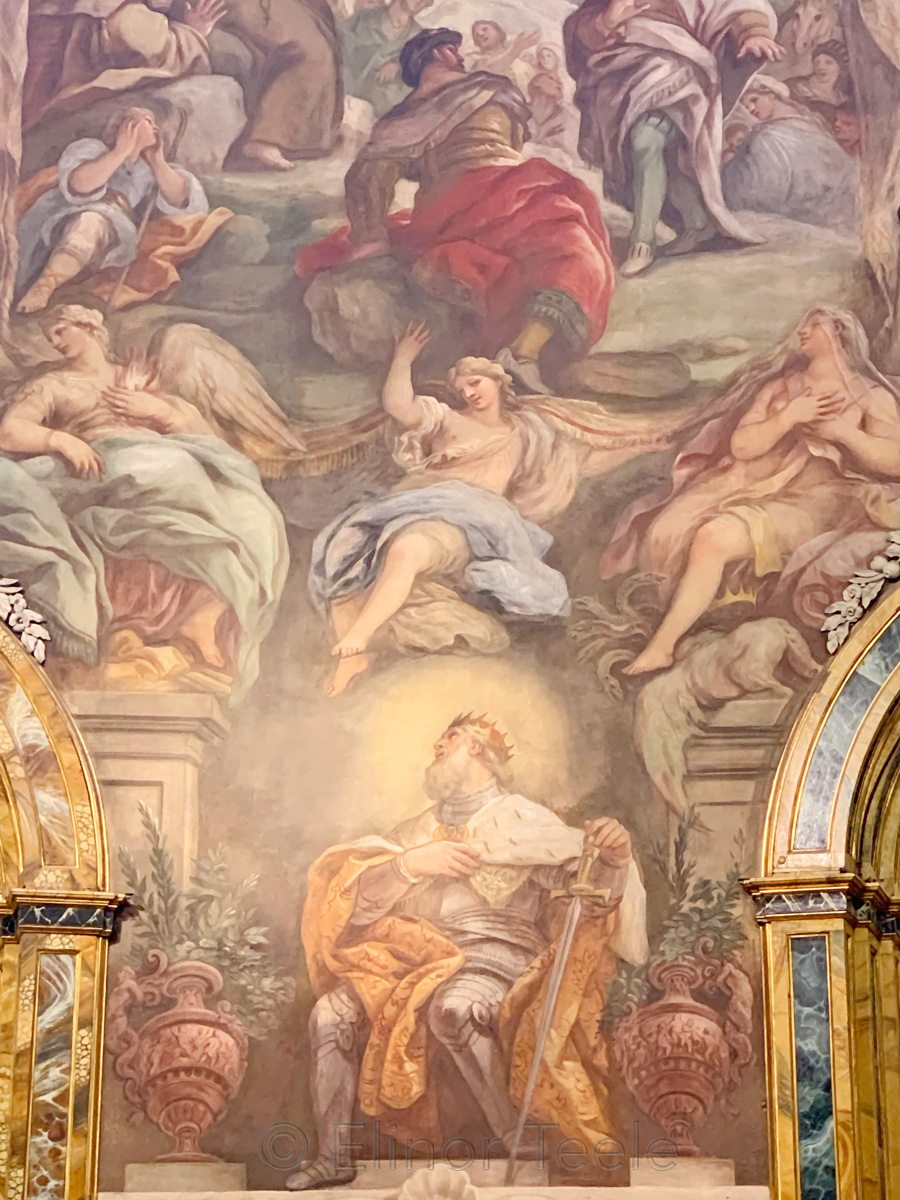

Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes | Church of St. Anthony of the Germans – Ceiling Close-Up, Madrid

The ceiling fresco is by Francisco Rizi. It depicts the Glory of St. Antony—the Saint is receiving the Infant Jesus from the hands of the Virgin Mary.

Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes | Church of St. Anthony of the Germans – Wall, Madrid

Most of the wall frescoes in the Iglesia de San Antonio de los Alemanes are by Luca Giordano. This marvel of the 17th century trained under Spain’s famous son, José de Ribera, and spent his years flitting around Naples, Rome, Florence, Venice, and Spain. During his life, he gained a

Museo Sorolla | Sorolla Museum, Madrid

The Museo Sorolla was Joaquín Sorolla‘s house, so it’s an intriguing way to get a sense of the man, his family, and his work. Even the garden reflects his love of light.

Museo de Historia de Madrid | Madrid History Museum, Madrid

This modest museum is one of the best places to understand Madrid as it was. As it is now, many of the buildings the city have been rebuilt, remodeled, refurbished, and removed from their roots. Even the street names have changed. At the museum, you’ll find plenty of everyday objects

Continue readingMuseo de Historia de Madrid | Madrid History Museum, Madrid