And there was the wail of my zither and the loud cry of my song for the death of the father…

Jews were active in Graz as early as the 13th century. They buried their dead in the old Jewish cemetery, near the present day Joanneumring. In a typical act of medieval insensitivity, a gravestone from this burial ground became an architrave block of the Archduke’s Burg. You’ll now find it embedded in the wall near the Double Spiral Staircase.

Jewish Gravestone Text (Rough Translation)

And there was the wail of my zither and the loud cry of my song for the death of the father, of my teacher, of Rabbi Nissim, son of Aharon, who entered into his eternity on Thursday the 10th, 147th month Tammuz, in the year of the sixth millennium.* May his soul be bound in the covenant of life. Amen. Selah.

* June 17, 1387 in modern dating.

Graz & Jewish History

Medieval Jews in Graz

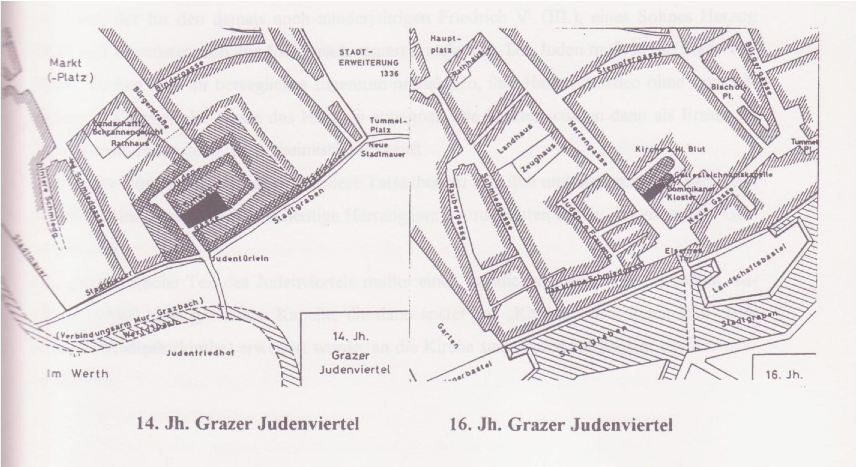

Medieval Jews lived in Graz’s Jewish quarter – a 100m x 140m square near the historic city wall. Carved into this wall was the Judentürl (“Jewish Gate”). Although the quarter, the wall, and the gate have long since been destroyed, you might sense their ghosts at the Am Eisernen Tor, where the Herrengasse begins.

Since the Catholic Church imposed tight restrictions on Christians taking interest, many Jews initially acted as moneylenders to the local nobility. The Graz community had a Jewish mayor, a Jewish judge, and – eventually – a synagogue. By the 15th century, the quarter had swelled to 200 people, around 4% of the city’s population.

And then it all went to custard. In 1438, the church loosened its rules about Christian moneylending. This put Catholics in direct competition with Jews.

The result was a pogrom. Jews were forced to leave their homes with whatever they could carry. They were only allowed back in 1447, when Friedrich III (the man who commissioned the Dom and indulged in heraldic graffiti) required their tax revenues.

A half century later, in a vicious program instituted by Maximilian I, all Jews in Central Austria were expelled for good. Huge Catholic debts were “miraculously” wiped off the books.

Modern Jews in Graz

It wasn’t until 1850 that Jews were permitted to resettle. Refugees from Eastern Europe swelled the ranks. A new synagogue was built along the river, and Chief Rabbi Dr. Gudemann gave the dedication:

“There is no conflict for us between our Judaism and our Germanism. May the new House of God be a guardian of loyalty to the Fatherland, of love for the mother tongue and for the culture of the Fatherland.”

But supporters of the Anschluss had a different idea of the “Fatherland.” During Kristallnacht, the synagogue was torched. 300+ Jews were deported to Dachau; 400+ fled the city. By June 1939, only 300 Jews remained. The hangers-on were eventually sent to Vienna and, from there, to death camps.

Today, you can visit the small synagogue on David-Herzog-Platz 1. This rests on the ashes of the one destroyed in 1938. But you won’t find many Graz residents in it. Approximately 100 Jewish people now live in the city, a fraction of the former population.

For more info on Jews in Graz, see: